A silver lining during the COVID-19 pandemic has been the dramatic rise of technology as an enabler for service delivery. Virtual meeting tools and software have transformed sectors – for example, tele-medicine in health, virtual schools in education and digital marketplaces for agriculture. In this article, we talk about the promise of virtual platforms to deliver maternal and child health interventions, highlighting three innovations from our work across remote and rural villages of India.

The Antara

Foundation (TAF) strengthens health systems to improve maternal and child

health. Our programs train community health workers (CHWs), make data-sharing

more effective, build supervisory capacity and improve health facilities. The

lockdowns and safety measures imposed due to COVID-19 caused a slowdown in

several program activities due to travel restrictions, limitations on holding

large group meetings and the unavailability of health workers because of

additional COVID-response duties.

To address

this, our team redesigned elements of the program to deliver select activities

remotely, to supplement in-person trainings and maintain continuity of our

interventions.

1. Virtual

capacity building to improve essential MCHN knowledge

Our

capacity building work improves knowledge and skills of CHWs on essential

maternal, child health and nutrition themes. Detailed assessments are carried

out to identify knowledge gaps and inform the curriculum. The format involves a

mix of group trainings and on-site handholding for weaker staff. During the

pandemic, short virtual training packages were designed, with visually engaging

modules and interactive content such as handouts and quizzes. Feedback from the

CHWs was very encouraging.

Such

targeted virtual sessions are now a core part of our capacity building approach

to supplement in-person trainings. Their success stems from the following:

first, virtual sessions can be more personalized, targeted and interactive; second,

sessions can be scheduled with more flexibility to accommodate health workers’

busy schedules; third, they require fewer resources compared to classroom

trainings; and they have the potential to transform into self-sustaining peer

learning groups in the future.

2. Virtual nurse mentoring for government birthing nurses

TAF’s nurse

mentoring solution plugs critical knowledge and skill gaps in nurses who

conduct deliveries in government labor rooms. The comprehensive training

package covers 48 modules across seven key themes and is delivered through a

series of classroom sessions and live demonstrations.

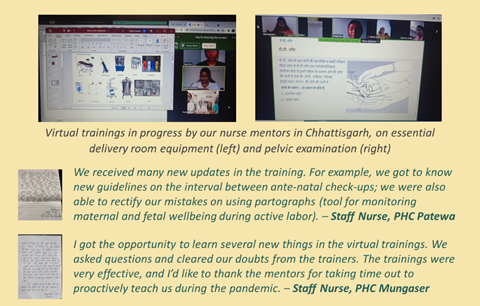

In our Chhattisgarh program, special virtual mentoring sessions were planned during COVID lockdowns to refresh concepts from previous trainings and discuss new modules. The format incorporated interactive case-based discussions, with pre and post online quizzes to increase engagement and ensure retention. The initiative proved immensely useful for the nurses to keep up to date and remain connected to their mentors and peers.

3.

Virtual AAA meetings

The AAA [Note 1] Platform is TAF’s flagship solution that brings the three community health

workers in each village on a collaborative data-sharing platform. The AAA

together create a detailed household level village map and mark critical

beneficiaries with different colored bindis. Each month, they meet to

pinpoint the highest-risk mothers and children, micro-plan service delivery,

and review each other’s work.

In

Chhindwara district, village maps have been created and installed in all ~900

villages of our focus blocks. Our team is now training the AAA to conduct

effective ‘AAA meetings’. During the lockdown, our team ran virtual AAA

meetings in select villages to help AAA identify high-risk beneficiaries,

develop follow-up plans, cross-check their data reporting, check availability

of medicines and supplies and recap essential knowledge.

The virtual

sessions involved collaborative discussion and data analysis. Several critical

action items were identified and promptly managed (e.g., anemic pregnant women

requiring urgent blood transfusion or iron sucrose, requirement for

antibiotics, iron and calcium tablets, vaccines).

We are enthusiastic about the early results from these targeted pilots. The willingness of health officials and CHWs to take to technology is encouraging. However, factors like device affordability, internet connectivity and basic IT skills are barriers still facing a large section of rural India. Until this ‘digital divide’ remains, scalability of purely virtual solutions will be a challenge. Meanwhile, we believe hybrid is the way to go, where technology supports and strengthens in-person grassroots health innovations.

Our

previous work in Rajasthan has shown the wonders technology can achieve. When

our ‘AAA Platform’ was taken up by the government for state-wide scale-up

across Rajasthan’s 46,000 villages, more than 125,000 CHWs were oriented

through video conferencing in a span of just a few weeks! Pilots of our ‘Integrated AAA App’ (mobile App for real-time data sharing

between CHWs) showed a significant increase in the identification of high-risk

mothers and children as compared to the offline process.

Note1: AAA

stands for ANM, ASHA and Anganwadi Worker – the three community workers who

deliver health and nutrition services in each village in India

Comments

Post a Comment